In programming

Luca Bianchini arrives at GO to sign copies of Le ragazze di Tunisi (Mondadori), a vibrant and colorful novel that moves and surprises readers, filled with family memories and hilarious anecdotes in a story shared by many Italians.

The Book:

“I didn’t truly know my mother’s family history until one day I started asking questions.” — Luca Bianchini

Tunis, 1959–1961. The Brancata family is one of the many Sicilian-origin families who went to Tunisia in search of America—and did not always find it. Instead, they lived peacefully alongside the French, who were still in power at the time, as well as Tunisians, Jews, and Maltese.

In this cosmopolitan setting, Maria—a beautiful, proud, and determined thirty-eight-year-old—watches her three teenage daughters grow up. She takes care of them on her own, as her husband works in the countryside and is almost always away. To cope with financial hardship, she takes on small sewing jobs at home in the Borgel neighborhood, on the ground floor of a building overlooking a courtyard where everyone knows everyone else.

Upstairs, a quiet widower courts her discreetly, but Maria is too busy keeping an eye on her girls—especially Anna, the eldest. Sixteen years old, Anna loves reading and watching ships on the horizon. Thanks to Uncle Jojo—the family’s charming Latin rogue who pays for her education—she attends one of the best schools in Tunis. Love still feels out of reach for her, but fortunately she has Marinette, her French friend, who introduces her to a world of cinema, beautiful clothes, and strolls along Avenue de France.

Constantly underfoot are her sisters: Vitina, who seems to think only about singing and gymnastics, and Pupetta, the family’s outspoken little voice of reason.

All around them is a lively city where the characters move through a suspended moment in time, caught between melancholy and uncertainty. With Tunisia’s independence, a season of farewells approaches for many. Yet it is precisely the fear of change that ignites hearts, sparks new stories, and reveals long-held secrets—within a microcosm of resentful uncles, curious neighbors, endless couscous, and anxious evenings spent in front of the television.

The Author:

Luca Bianchini was born on February 11, 1970, in Turin. He still writes in the kitchen, although he has yet to learn how to fry food as well as his mother.

Since 2003, Mondadori has published all his novels: Instant love, Ti seguo ogni notte, the biography of Eros Ramazzotti(Eros – Lo giuro), Se domani farà bel tempo, Siamo solo amici, Io che amo solo te and La cena di Natale—both adapted into highly successful films—Dimmi che credi al destino, Nessuno come noi (later brought to the big screen), So che un giorno tornerai, Baci da Polignano, Le mogli hanno sempre ragione, and Il cuore è uno zingaro.

Vera Buck comes to GO for the signing of Buio (Giunti), her latest thriller — a novel that will keep you glued to the pages with its unforgettable characters, breathtaking setting, and haunting atmosphere.

The book:

A house for one euro: for Tilda, a young German woman of Italian origin, it feels like an incredible stroke of luck. She wants to cut ties with her previous life, and a villa in Sardinia seems perfect. Botigalli is every restoration-loving architect’s dream: an abandoned village perched high in the mountains of Barbagia, around fifty houses and a single road leading to a picturesque church.

It also represents a radical change — manual labor, solitude, and good food.

But the idyll of this place suspended in time does not last long. The village, which at first seemed completely deserted, begins to stir in unsettling ways: strange noises, objects moved from their places, and then a terrible secret dating back to the summer of 1982 — the year of the World Cup and the Italy–Germany final — when a shooting left all its inhabitants dead.

No one truly knows what happened that day, and the only survivor, the elderly Silvio, stubbornly refuses to speak, even though a journalist visits him every Sunday trying to persuade him to tell his tragic story. And Tilda, despite herself, will suddenly find herself pulled into it.

Bringing light into the darkness of those years will be the only way to get out… unharmed. Because in this harsh and isolated land, terrible things have happened — and are still happening.

The author:

Vera Buck is a German author. She studied journalism, literature, and screenwriting in Europe and Hawaii, and worked as a freelance writer in Zurich.

Bambini lupo, published in Italy by Giunti in 2024, marked her debut in the thriller genre and was both a critical and commercial success in Germany. She has also published La casa sull'albero (2025) and Buio (2026) with Giunti.

Lyra Sunrise is coming to GO for the signing event of her debut novel Twist of Fate, Vol. 1 – Obsession (Sperling & Kupfer)!

Preorders of the book, which will grant you a pass, can be placed in our bookstore starting Friday, February 6.

Useful information

Here’s how the signing event will work:

-

The priority pass is available with a preorder of the book made in our store only, or with the purchase of the book in-store only from the release date up to the day of the event. Passes will be distributed in time slots.

-

To access the priority line, you must show your pass (with the correct time slot) to the staff member in charge.

-

Once the priority line is finished, everyone else who did not purchase the book from us (and therefore does not have a pass) will be able to access the signing.

The book

Delia Foster has learned how to survive. Raised in the shadow of an absent mother and a past that broke her, she built an armor to protect herself and chase her dreams. But when she flies to New York with her best friend Lynn to start over, fate has another challenge in store for her.

Her path crosses with the Harris brothers, heirs to the most powerful multinational company in America: Alexander, thirty-six, with icy eyes; and Erik, as charming as he is impulsive, trapped in a relationship he never chose.

Delia becomes Alexander’s personal assistant—the man she should hate, yet desires with every fiber of her being. Lynn, meanwhile, is forced to confront Erik’s truth, his anger, and his need to finally be himself.

As the line between passion and danger grows thinner, the four are drawn into anonymous threats and secrets someone is ready to expose. And to survive, they’ll have to choose which side to stand on.

The author

Lyra Sunrise is the pen name of a young author from Naples, born in 2007. Since childhood, she has taken refuge in love stories from movies, books, and TV series—where her passion for writing was born. Twist of Fate is her debut novel.

Film History Workshop curated by Marco Luceri: Great Italian Cinema (1945-1975) - Meeting no. 4

1945-1975: this was the golden age of Italian cinema, full of masterpieces that left their mark on the entire history of film. From the ruins of war arose Neorealism, the “movement” that, with Rossellini, Visconti and De Sica-Zavattini, changed the way cinema was made and conceived forever. From the early 1950s, the revolutionary charge of Neorealism faded, becoming contaminated with popular genres such as comedy and other forms of popular cinema, passing through the golden 1960s with the affirmation of great auteur cinema (Fellini, Antonioni, Pasolini, etc.), “Italian-style comedy” and other genres (such as spaghetti westerns), until the anxieties, experiments and new sensibilities of the early 1970s. A long history in which Italian cinema reflects and reworks the enormous political, social, economic and cultural changes experienced by the country during those crucial three decades.

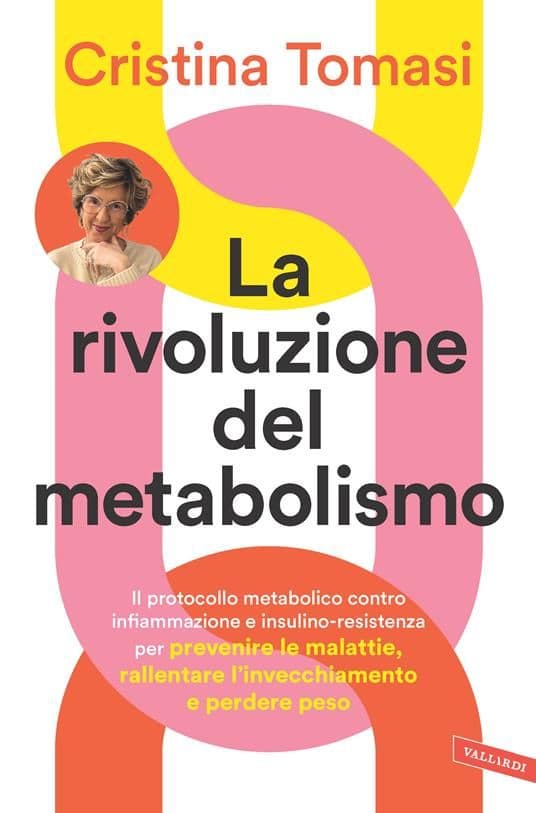

Cristina Tomasi will be joining us for a talk entitled LA DONNA AL CENTRO, where she will discuss her latest book La rivoluzione del metabolismo. Il protocollo metabolico contro infiammazione e insulino-resistenza per prevenire le malattie, rallentare l’invecchiamento e perdere peso (Vallardi).

The Book:

Most people suffer from metabolic imbalances without even realizing it. The signs? Difficulty losing weight, persistent fatigue, sleep disturbances, hormonal issues, and chronic inflammation. Over time, these imbalances increase the risk of conditions such as diabetes, autoimmune diseases, and cardiovascular disorders.

With more than thirty years of clinical experience and an approach grounded in the latest scientific evidence, the Tomasi Method offers a comprehensive solution to reprogram the metabolism and restore natural well-being. Through targeted nutrition plans and daily practices, this book helps you reactivate your metabolism to lose weight, reduce chronic inflammation and insulin resistance, improve sleep quality and energy levels, and reverse cellular aging processes.

BECOME THE PROTAGONIST OF YOUR HEALTH

The Tomasi Method guides you in restoring metabolic balance through:

-

Personalized and sustainable nutritional strategies

-

Precise techniques to optimize sleep and hormonal response

-

Specific protocols to manage inflammation and insulin resistance

-

An integrated approach combining nutrition, movement, light exposure, and stress management

The Author:

Cristina Tomasi is an Italian medical doctor specializing in Internal Medicine and Angiology. After serving as Deputy Head Physician in Internal Medicine and completing several advanced master’s programs (she is an expert in bioequivalent hormone therapy), she founded the platform Top Life Project Srl to promote scientific knowledge and empower individuals to take charge of their own health.

She is a widely followed author on social media, with nearly one million followers across Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok.

Among her published works are:

Non è solo questione di ormoni. Ritrovare vitalità e benessere psicofisico dopo i 40 anni con dieta, stile di vita e ormoni bioequivalenti (Red Edizioni, 2023), and La rivoluzione del metabolismo. Il protocollo metabolico contro infiammazione e insulino-resistenza per prevenire le malattie, rallentare l’invecchiamento e perdere peso (Vallardi, 2025).

Roger Abravanel and Luca D’Agnese present at GO Le grandi ipocrisie sul clima (Solferino), an illuminating and provocative essay that sheds light on both the strengths and weaknesses of the Italian economy in addressing the climate emergency. While the potential for innovation is considerable, the country’s ability to fully capitalize on it remains too weak.

Joining the authors on stage will be Andrea Marchetti, Headmaster of the Istituto agrario Le cascine; Alessandro Artini, President of ANP Toscana; Giampaolo Marchini, President of the Order of Journalists of Tuscany; Ferruccio de Bortoli, President of the publishing house Longanesi and of the association Vidas; and journalist Raffaele Capparelli.

The event will be moderated by Marcello Mancini, former director of La Nazione and President of the Scientific Committee of the Foundation of the Order of Journalists.

The Book

The planet is at risk. As the climate emergency manifests itself in all its severity, corporate commitment to sustainability has surged. Recently, however, growing skepticism has emerged toward the bureaucracy created in the name of environmental and social responsibility, known in companies by the acronym ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance).

The clash between enthusiasts and skeptics is dangerous because it generates a new form of climate denialism—one that acknowledges the problem but seeks to postpone solutions until they cost less, or believes that only the State should take responsibility.

The opposing mistakes of enthusiasts and skeptics are fueled by several dangerous hypocrisies. The hypocrisy of the neo-denialists, who claim to be concerned but ultimately propose only superficial initiatives. And the hypocrisy of the new sustainability “gurus,” who theorize a new “good” capitalism that in reality blends some sound principles long followed by responsible entrepreneurs with the claim that profit objectives should be relegated to the background.

What is needed instead is a new approach, as proposed in these pages: a “sustainability triangle” that has already achieved previously unthinkable progress on climate issues. This model calls for a new corporate mindset to seize the innovation opportunities offered by the planet, a qualitative leap in states’ economic policies, and a more pragmatic attitude from activists, who are too often driven by ideological extremism. At its core is a return to the original idea of sustainability—distinguishing true crises, which will inevitably explode if left unaddressed, from the countless other social and environmental problems in the world that businesses cannot be expected to solve.

The Authors

ROGER ABRAVANEL is Director Emeritus of McKinsey, an entrepreneur and investor in technology startups, and a board member of international companies, where he leads sustainability committees.

He is also a columnist for Corriere della Sera and an essayist. Among his books: Meritocrazia (2008), Aristocrazia 2.0(2021), and, with Luca D’Agnese, Regole (2010), Italia, cresci o esci! (2012), and La ricreazione è finita (2015).

LUCA D’AGNESE is Director of CDP Infrastructures, Public Administration and Territory at Cassa Depositi e Prestiti. He also works in infrastructure advisory. Previously, he held positions at Hewlett-Packard and McKinsey. He served as CEO of the National Transmission Grid Operator and, in 2007, became CEO of ErgyCapital.

With Roger Abravanel he co-authored Regole (2010), Italia, cresci o esci! (2012), and La ricreazione è finita (2015).

LIVING WITH THE TIMES – A Dialogue on Jonathan Sacks’ Commentary on the Bible, “Alleanza e Conversazione”

At Giunti Odeon, Living with the Times: a dialogue on Alleanza & Conversazione by Jonathan Sacks (Giuntina).

Participants will include Mons. Gherardo Gambelli, Archbishop of Florence; Rav Gadi Piperno, Chief Rabbi of the Jewish Community of Florence. The discussion will be moderated by Shulim Vogelmann, publisher of Giuntina. Greetings will also be offered by Sara Funaro, Mayor of Florence.

Genesi. Il libro dei fondamenti:

Bereshit, the Book of Genesis, speaks to us of origins: of the world, of humanity, of the family. Yet it is also the foundation of the Jewish experience and, at the same time, a universal narrative capable of addressing every human being, beyond all religious or cultural boundaries. Genesis confronts the great themes of the human condition—freedom, responsibility, justice, faith, and our relationship with others—through vivid, deeply human stories that continue to challenge the present.

In this first volume of the series Alleanza & Conversazione, Jonathan Sacks guides the reader by masterfully weaving Jewish wisdom together with philosophy, literature, and contemporary thought. With clarity and depth, Sacks invites us to discover how the stories of Genesis—from Creation to the Flood, from Babel to the call of Abraham, and through the deeply meaningful lives of the patriarchs and matriarchs—continue to speak to us today. His is a precious invitation to join the millennia-long conversation between heaven and earth, between God and humanity, in order to live our own time with awareness and hope.

Esodo. Il libro della redenzione

Shemot, the Book of Exodus, recounts the story of a people enslaved and oppressed for generations, who ultimately break free from the chains of the most powerful empire of the ancient world. This narrative carries revolutionary meaning: it presents a God who stands with the oppressed and the voiceless, and it celebrates the birth of the Jewish people, called to build a new society founded on justice and fairness. From slavery in Egypt to the plagues, from the leadership of Moses to the giving of the Torah, from the idolatry of the Golden Calf to the construction of the Tabernacle, Exodus continues to speak to us about freedom, responsibility, and the equal dignity of every human being.

In this second volume of the series Alleanza & Conversazione, Jonathan Sacks restores to Exodus its visionary power—the same power that inspired movements of liberation and struggles for civil rights. A message that remains profoundly relevant today, speaking of hope and of a society founded on integrity and mutual respect.

The Author:

Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks (1948–2020) was a globally recognized religious leader, philosopher, and moral voice of our time. Author of more than twenty-five books, he received sixteen honorary degrees and numerous awards for his work. He served as Chief Rabbi of the United Hebrew Congregations of the Commonwealth from 1991 to 2013. Giuntina has previously published Non nel nome di Dio and Moralità, to which are now added Genesi. Il libro dei fondamenti and Esodo. Il libro della redenzione, the first volumes of the series Alleanza & Conversazione.

Film History Workshop curated by Marco Luceri: Great Italian Cinema (1945-1975) - Meeting no. 5

1945-1975: this was the golden age of Italian cinema, full of masterpieces that left their mark on the entire history of film. From the ruins of war arose Neorealism, the “movement” that, with Rossellini, Visconti and De Sica-Zavattini, changed the way cinema was made and conceived forever. From the early 1950s, the revolutionary charge of Neorealism faded, becoming contaminated with popular genres such as comedy and other forms of popular cinema, passing through the golden 1960s with the affirmation of great auteur cinema (Fellini, Antonioni, Pasolini, etc.), “Italian-style comedy” and other genres (such as spaghetti westerns), until the anxieties, experiments and new sensibilities of the early 1970s. A long history in which Italian cinema reflects and reworks the enormous political, social, economic and cultural changes experienced by the country during those crucial three decades.

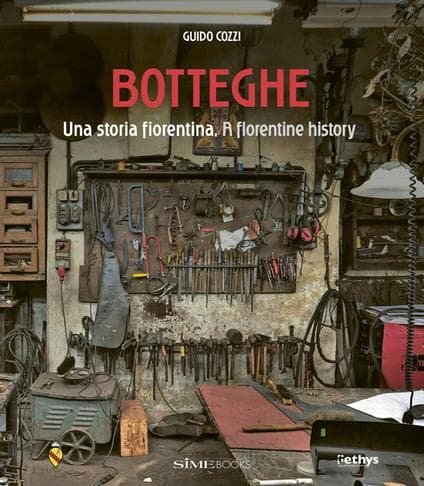

At GO, the presentation of the bilingual volume Botteghe. Una storia fiorentina. A Florentine History (SIME BOOKS) will take place.

The presentation will feature photographer Guido Cozzi, who created the images included in the book, and Livia Frescobaldi, President of the Istituto de’ Bardi, who last year presented the exhibition of Cozzi’s photographs from which the idea for the book was born.

The event will be hosted by Chiara Dino of Corriere Fiorentino.

The Book:

Botteghe. Una storia fiorentina is a photographic book, a journey through the last remaining artisan workshops in the heart of Florence. It is also a tribute to the workshops that no longer exist but have left an important legacy.

A red thread to follow in order to rediscover the filigree of an authentic Florence—sometimes difficult to decipher because it is hidden, yet no less beautiful or significant for that reason.

The Author:

Guido Cozzi

Born in Florence in 1962. For specialized publishing, he has produced hundreds of photographic features of a geographical, ethnographic, and travel nature. In 1991, together with Stefano Amantini and Massimo Borchi, he founded Atlantide Phototravel, a photographic agency specializing in travel reportage.

Today he alternates photographic campaigns for major international archives with personal research projects in his local area, experimenting with different narrative styles according to the subject explored.

After the success of Selvaggio Ovest, Daniele Pasquini returns to GO with La fine della frontiera (NN Editore), a work that intertwines the western and the historical novel, where identity, choices, and destiny are measured against the course of history. It is a story of men and women searching for a place in the world and for something worth living — or dying — for. For this presentation, the author will be joined by Nicoletta Verna.

The book:

In 1861, Italy is a newly unified nation, and America promises an endless future. Dante Niccolai, a young Tuscan cart driver left orphaned, leaves his home to accompany the Ferrini family to the port of Genoa and decides to embark with them for the New World, chasing the mirage of a better life. Between him and Adele Ferrini an epistolary relationship is born, made of promises and long ожидations, but the vastness of the continent divides them: Dante wanders for years through the heart of America, while Adele finds a new identity among the Cheyenne. Their stories intertwine with History and with the adventures of Carlo Di Rudio, a Mazzinian revolutionary who escaped the guillotine and forced labor, and who chooses the West as his final trench. And as the white offensive culminates in the legendary Battle of Little Bighorn, symbol of Native resistance, a web of guilt, betrayal, and violence — bearing the name of the ferocious Iron Jack — binds together the destinies of Dante, Adele, and Carlo. La fine della frontiera is a historical and adventure novel, where the wandering lives of its protagonists stand out against the sunset of the myth of the West. With the clear voice of someone telling stories by a fire, Daniele Pasquini reminds us that life is a great battle already lost — but when the heart runs like a galloping horse, we can only mount up and ride.

This book is for those who travel for the pure pleasure of getting lost, for those hoping for another prequel of Yellowstone, for those who feel in their gut the rumbling of swallowed words, and for those who have discovered that a powerful desire is at once a condemnation and a blessing — a hunger for light that pushes us to march beyond the horizon.

The author:

Daniele Pasquini was born in 1988 in the province of Florence and works in publishing communication. He made his fiction debut in 2009 with Io volevo Ringo Starr, followed by a short novel and a collection of stories, all published by Intermezzi Editore. In 2022 he published Un naufragio with SEM. For NNE he published Selvaggio Ovest (2024), winner of the Selezione Bancarella Prize, finalist for the Alessandro Manzoni International Literary Prize, and finalist for the Asti d’Appello Prize.

A place of history and beauty

Since 1922, the most beautiful films, the most distinguished guests, and the most remarkable events have taken the stage at the magnificent cinema-theatre in Piazza Strozzi, Florence. Come visit us.

Odeon, a century of cinema and culture.

A book filled with images, documents, stories, and curiosities retraces the history of one of Florence's most iconic places, from its origins to the present day. Discover more.

Exclusive benefits

With the GO Card, enjoy the benefits of Giunti al Punto bookstores and the exclusive experiences of Giunti Odeon. Coming soon.